Joseph Ogierman

Consultant

Download this article as a PDF (5.2 MB); cite as MESA Journal 95, pages 49–59

Published December 2021

Introduction

In 2020–21 the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 challenged many industries including the mineral resources sector. Working from home became a norm. Many exploration geologists turned their attention to desktop studies in preparation for the anticipated recommencement of on-ground activities. Desktop reviews – trawling through databases recording previous mineral exploration results – can prove very beneficial in providing new exploration targets, presenting an opportunity to step back and reassess a province or prospect in a different light using new geological models or refining existing ones. Yet it can also have the opposite effect, leading the reviewer to downgrade the project’s potential due to technical, financial or corporate objectives. There can be an understandable temptation to devalue the potential of a project if there is a perception that sufficient work has been done in the past by prospectors or exploration companies using ever more sophisticated techniques.

In the first decade of this century, the success of Terramin Australia Ltd in bringing the small, high-grade polymetallic Angas mine, near Strathalbyn, South Australia, to production is an example of how persistence paid off in finding a deposit which had been repeatedly missed or dismissed by prospectors, farmers and geologists. Located in terrain that has been densely cultivated for over 150 years, its true potential was realised in the early 21st century, in part due to the very low-tech and low-cost method of reviewing historical data online.

Regional geology and mineralisation

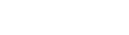

Figure 1 Distribution of base and precious metal (Cu–Au, Pb–Zn–Ag, Fe sulfide deposits) in the Tapanappa Formation of the Cambrian Kanmantoo Trough along the southern margin of the Neoproterozoic Adelaide Rift Complex.

The Angas deposit (3.04 Mt at 8.0% Zn, 3.1% Pb, 0.3% Cu, 34 g/t Ag, 0.5 g/t Au), located 45 km southeast of Adelaide (Fig 1), sits within the Kanmantoo Trough, a linear fault-bounded basin which formed along the southeastern margin of the Neoproterozoic Adelaide Rift Complex during late Neoproterozoic break-up of the Rodinia Supercontinent. The basin hosts Cambrian Kanmantoo Group metasediments, a 7–8 km thick pile of rapidly deposited psammitic and lesser pelitic rocks laid down between 526 and 514 Ma (Jago et al. 2003). Sedimentation ceased at 514 Ma with the onset of deformation, triggered by tectonic reversal of the eastern edge of the supercontinent Gondwana from a passive margin to active subduction (Rosenbaum 2018).

The resulting Cambrian–Ordovician Delamerian Orogeny (514–490 Ma) inverted both the Adelaide Rift Complex and Kanmantoo Trough sedimentary sequences into a west-verging fold thrust belt (Flöttmann et al. 1994). At least 3 regional deformation events are recognised (Belperio et al. 1998), with D2 producing dominant structures in the Strathalbyn region expressed as upright to inclined major folds, generally north–south striking and plunging shallowly southwards. Metamorphism reached its peak grade pre- or syn-D2, with partial melting and development of migmatites to the north of Strathalbyn, where deformation was accompanied by bimodal magmatism in some places (Foden et al. 2002), decreasing to amphibolite grade elsewhere in the Kanmantoo–Strathalbyn area (Offler and Fleming 1968).

Polymetallic mineralisation is confined to 2 unique horizons within the Kanmantoo Group:

- pyritic metapelites of the Talisker Formation – including the undeveloped Mount Torrens prospect (0.7 Mt at 8.0% Pb + Zn, 41 g/t Ag) and Brukunga pyrite mine (~32 Mt at 18% FeS with strongly anomalous Zn–Pb) (Fig 1)

- a stratigraphic interval within the overlying Tapanappa Formation, several hundred metres wide, hosting the majority of base metal mines.

The majority of base metal deposits within the Tapanappa Formation are either: (i) Cu-rich and discordant to stratigraphy, such as the area surrounding Kanmantoo township, 32.2 Mt at 0.9% Cu + 0.2 g/t Au (Hillgrove Resources 2012); or (ii) stratabound Pb–Zn–Ag (± Cu) along a unique garnet–gahnite-rich zone, known informally as the ‘host unit’ or ‘lode horizon’. Both deposit types are hosted by a stratabound, regionally metamorphosed hydrothermal alteration zone consisting of quartz–biotite–garnet–andalusite ± staurolite and garnet–andalusite–biotite–staurolite schist that extends intermittently for >30 km in the Kanmantoo–Strathalbyn area (Tott et al. 2019). This zone contains meta-exhalative rocks in the form of banded garnet (Mn) – quartz (‘coticules’), quartz–magnetite, quartz–garnet–cummingtonite, banded iron formation along with quartz–gahnite rocks, tourmalinite and metachert (Spry 1976; Toteff 1999; Pollock et al. 2018; Tott et al. 2019).

Mine geology

The Angas deposit is located along the eastern limb of the Strathalbyn Anticline, at the southern outcropping extremity of the host unit, only 2.5 km east of Strathalbyn township. The dominant host lithology is graywacke with minor pelite horizons, which are crosscut by rare post-Delamerian dolerite dykes. The lodes consist of one main and several smaller, east-dipping and south-plunging, stratabound massive sulfide lenses, aligned subparallel to both bedding and the dominant S2 schistosity. The Main or Rankine Lode consists of a south-plunging linear body of massive and disseminated Pb–Zn–Fe–Cu sulfides, about 500 m in length, 150 m to 200 m wide, and from 1 m to over 10 m thick. The enveloping psammitic/pelitic host unit has a characteristic mineral assemblage consisting of fine-grained, euhedral pink Mn-garnets ± staurolite, andalusite, sillimanite, cordierite and, most significantly, Zn-rich spinel–gahnite. The host unit varies in width from 25 up to 200 m, reflecting pinch and swell or boudinage development.

The sulfide ore consists of medium to coarse-grained sphalerite–galena–pyrite–pyrrhotite with minor chalcopyrite. Grain boundary textures indicate the sulfide mineral assemblage reached equilibrium at peak amphibolite-grade metamorphic conditions (Pontifex 1992), and during ongoing deformation was partially remobilised and preferentially concentrated within low-strain zones during boudinage development of the host unit (Laing 1998; Ogierman 2004).

History of discovery

19th century

During the 1840s the Mount Lofty Ranges were the location of Australia’s first mining era (Drew 2011). At a critical period in the development of South Australia, when the new colony was on the verge of bankruptcy, silver–lead was discovered at Glen Osmond, only 6 km from the Adelaide GPO. Within a few years more significant mines, predominantly copper, were discovered first at Kapunda (1842) and then at Burra (1845). These discoveries created great excitement in the colony, with the Adelaide Observer newspaper (1861) stating ‘Were our South Australian copper mines worked with sufficient enterprise, vigour, capital and labour, we might supply the whole world with copper’. People looking for rich pasture lands beyond the Adelaide Plains were also keeping an eye out for mineral treasures.

News of these discoveries reached London, encouraging the South Australia Company, which was formed to colonise the state, to become involved in the ‘copper fever’. Aiming to explore the Mount Barker district, they employed 2 Cornish miners who in 1845 reported to the company’s geologist, JC Dixon, they had discovered a ‘rich deposit of copper ore’ at Kanmantoo (Drew 2011).

The following year, in 1846, mining operations commenced at Kanmantoo and at a number of other mines, many with names reflecting the Cornish heritage of migrants attracted to the colony by news of the copper boom. ‘Wheal’ is Cornish for ‘mine’ or ‘working’, and the hills surrounding Kanmantoo were soon host to Wheal Mary, Wheal Friendship, Wheal Prosper and others. Miners followed mineralisation trends south from Kanmantoo, making finds that were progressively closer to the township of Strathalbyn, 20 km away.

Strathalbyn had been founded in late 1839 by Dr John Rankine, who had sailed from Liverpool on the Fairfield earlier in the year. The township became the centre for a burgeoning pastoral and farming district and, as with other Hills communities, settlers kept a lookout for the tell-tale colour of oxidised ore minerals, as well as for good farming soil. They were rewarded in 1846 with a discovery of copper and then of silver–lead just 2.5 km northeast of Strathalbyn, on Dr Rankine’s land. The Strathalbyn Mining Company was formed to work the 2 mines, which together became known as the Strathalbyn mine. Unfortunately, the ore proved refractory and difficult to smelt, all but curtailing work on the mine, but not before it had promoted exploration in the district. In May 1848, the South Australian newspaper published in Adelaide suggested the Strathalbyn mine lay along the same ‘line of lode as the Kanmantoo and Burra mines’, and that there was a ‘probability of mines being found south of Strathalbyn at Encounter Bay’. Somehow though, even with such encouragement, prospectors, townsfolk and farmers managed to miss the gossan which marks the outcrop of Angas mineralisation only 800 m south of the Strathalbyn mine. It was the first time Angas was missed.

Australia’s first mining era, largely built on South Australian copper, ended in 1851 with discovery elsewhere of gold, causing an exodus of miners, tradesmen, farmers and other townsfolk to the newly discovered Victorian goldfields 550 km to the southeast. According to the Southern Argus newspaper published in Port Elliot, ‘Men could not be detained on the works for love or money, the gold fever having got a sudden and rigid hold of one and all with ambition for wealth, and the mines were deserted’.

Not everyone left, however, and of those that did, some returned after a few years when their ‘ambition for wealth’ had not materialised. Prospecting continued along the Kanmantoo–Strathalbyn corridor, and in 1856 a discovery of silver and lead was made at Wheal Ellen, 8 km north of Strathalbyn, resulting in mining operations commencing there in 1857, employing up to 100 men. Over the following decade this mine produced 8,000 t of ore with nearly 200,000 oz of silver recovered. Unfortunately, as with the Strathalbyn mine, the presence of significant amounts of zinc caused metallurgical recovery issues for lead and silver, because the technology to recover zinc separately was not yet available. Prospectors were undaunted, however, and discoveries locally continued to be made.

On 27 February 1869 the Southern Argus newspaper reported ‘a mineral discovery made on Mr Allan MacLean’s property near the swamp about a mile to the southward of the workings of the old Strathalbyn mine’. That swamp is the historical Meadowbank Swamp, located 2.5 km east-northeast of Strathalbyn, now at the intersection of Swamp Road with Callington Road. The press article continued: ‘Mr MacLean commenced sinking on a reef which can be traced for miles and struck a vein or leader which at 2 fathoms developed into a well-defined lode 3 feet in width. At a depth of 3 fathoms the lode widened to between 4 and 5 feet. Two samples were taken and one gave a result of 15 oz silver and 8 dwt gold, and the other 1 oz silver and 5 dwt gold to the ton.’

Although there are no maps showing the location of this discovery, a shaft can still be seen today just north of what used to be the Meadowbank Swamp. More recently, in the 1980s, earthworks were undertaken by the District Council of Strathalbyn to modify the swamp into wastewater treatment lagoons, but the old mine is still visible. Subsequent exploration drilling carried out by Terramin in 2004 showed the Angas orebody, when its lodes are projected to the surface, outcrops at the site of this shaft suggesting the Angas deposit was indeed discovered in 1869.

The Southern Argus article continued: ‘The lode presents a pretty appearance and will repay a visit. We believe it is intended to form a preliminary company to further test the property and then offer it to the public’. There is no further mention of the discovery, either in newspapers or South Australia Mines Department records, so we can assume it was never developed or offered to the public. There is only conjecture as to why; it is possible the lode narrowed at depth, or perhaps the miners recognised the ore was similar to Strathalbyn and Wheal Ellen mines, and therefore would have similar smelting issues due to the presence of zinc. Either way, after finally being discovered, the Angas orebody was dismissed for the first time.

The remainder of the 19th century saw little prospecting activity in the Strathalbyn area. Low metal prices in the 1880s, coupled with persisting metallurgical difficulties in treating lead–zinc ore, and the knockout blow of a severe economic depression in 1892–93, meant little appetite existed in the state for developing base metal mines. Consequently, the Angas orebody lay dormant after first being missed and then becoming dismissed in the course of the 19th century.

20th century (pre-1950)

At the start of the new century a combination of higher metal prices due to a buoyant global economy and improved metallurgical techniques caused renewed optimism. Of particular relevance to the Kanmantoo Trough was an improved knowledge of dealing with zinc in polymetallic ores, to a point where it became an economic positive, not a hinderance. The potential of the flotation process to deal with complex, refractory ores such as those at Wheal Ellen and Strathalbyn mines encouraged investors to raise capital and recommence operations. ‘So great have been the strides in this direction that matter — such as zinc sulfide — which was previously a source of trouble and much anxiety has become of high value, and, as in the case of Broken Hill, this metal bids fair to become a big factor in the dividend capabilities of the mines in the future’ (Southern Argus 1906).

However, as is the case with any mining boom, regardless of the period, caution is necessary to separate reality from spin. Many promoters were active in Adelaide at the start of the century, and articles appeared in newspapers extolling the potential of reopening abandoned mines that had previously suffered from an exodus of miners to Victorian goldfields and from metallurgical issues caused by zinc. Nevertheless, the start of the 20th century ushered in the promise of a new mining boom in South Australia through the use of modern metallurgical knowledge and techniques.

In 1906 the Southern Argus reported, ‘considerable attention is being devoted to the metalliferous belt of country running northerly from Cape Jervis and hugging the Adelaide Hills and propositions for reopening of several mines in the vicinity of Strathalbyn are afoot. The most notable of these is the Strathalbyn mine (silver–lead and zinc), 2 miles north of the town.’ It went on to suggest that once the old mines were cleared of debris, and ‘if the ore body is only one-half of what the available reports declare it to be, then a fortune awaits the shareholders’. The orebody was reported to be 18 feet in width assaying 18% lead and 16.5 oz silver per ton, and sampling of dumps by the School of Mines returned ‘from 88 to 44 per cent zinc and gold in appreciable quantities must also be contained in the ore because lead bullion picked up at the smelter site gave an assay value of 4 oz per ton’. The distinction between reporting and advocating became evident, with the author suggesting ‘there seems no doubt whatever that a great and prosperous future awaits the enterprise. The basis of the flotation is 500 shares of £5 each … The prospectus will be found in our advertising columns’. Indeed, the abridged prospectus can be found in the advertising section of the Southern Argus next to a notice of a church strawberry fete, a clothing sale from Melbourne and a dentist spruiking his new denture-making technique that can produce a ‘more youthful effect on a face by filling out lips and sunken lines’. Perhaps the fortune to be made from buying shares in the Strathalbyn mine could be used to enhance one’s appearance.

It is possible a successful reopening of Strathalbyn mine would have encouraged nearby prospecting, possibly thereby revisiting the unknown mine on MacLean’s property only 800 m to the south. However, the initial rush of enthusiasm marking the start of the 20th century just as quickly faded, with little work done on any of the reopened silver–lead–zinc mines between Kanmantoo and Strathalbyn. Fresh efforts to rework the Aclare mine were tried in 1906 and again in 1912, with little success; the Wheal Ellen mine was acquired in 1907 by a syndicate from Sydney, who ignored the silver–lead–zinc potential and instead mined 5,000 t of pyrite to produce sulfuric acid and erected a 5-head stamp battery for recovery of 404 oz of gold from gossan and pyritic ore. As for the Strathalbyn mine, the promise of fortunes awaiting shareholders was but a mirage as, although some new shafts were dug, underground drives extended and a winding plant erected at the surface, operations ceased after just one year. Those initial restart efforts were not helped by unwilling landowners who were averse to any mining taking place and ‘and at the first chance had the shafts filled up by huge trees being thrown in endways, making the labour of clearing very difficult’ (The Advertiser, 18 Oct 1906). Conflict between miners and farmers in the Adelaide Hills has a long history, which continues to the present day.

In May 1908, The Advertiser announced a voluntary winding up of the Strathalbyn Silver Lead and Zinc Mining Company, ending any motivation to prospect the surrounding area. Exploration activity in the Strathalbyn region dried up for the following 5 decades, and the district matured as a centre of agricultural production. The gently rolling hills which overlie the Angas orebody were planted with cereal crops and used to graze sheep.

20th century (post-1950)

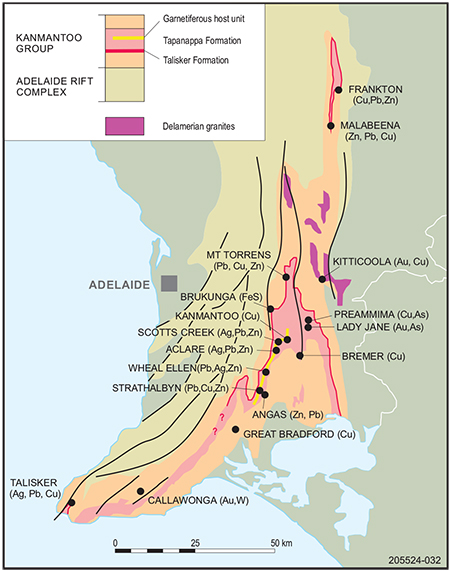

Figure 2 Geological map of a portion of the Kanmantoo Group sediments lying between Strathalbyn and Kanmantoo, showing location of historical base metal mines along the garnet-rich interval known as the host unit.

Following the end of the Second World War, prospectors and explorers returned to the Kanmantoo Trough and the province eventually became tested by modern exploration techniques. The South Australian Mines Department led the charge, attempting in the early 1950s to generate interest for base metals by investigating historic mines between Kanmantoo and Strathalbyn (Fig 2). Cochrane (1952) inspected the Wheal Ellen and Strathalbyn mines and following his recommendations, 2 diamond drillholes were completed by the department at the latter. Thin zones of massive sulfides and wider zones of disseminated zinc-rich mineralisation were intersected. Electrical geophysical surveys were undertaken on the surface, and although results were not encouraging, mining companies soon followed this lead to begin work in the Kanmantoo Trough. BHP South subsidiary Mines Exploration delineated a 12 Mt low-grade copper resource under the old Kanmantoo workings. The resource was partially mined between 1970 and 1976, ushering in a new era of mining.

Modern exploration methods were accompanied by the application of conflicting new geological models for the origins of mineralisation, starting a debate which continues to this day almost 50 years later. One school of thought regards mineralisation to be a late-stage product accompanying the Delamerian Orogeny (Thomson 1975; Parker 1986), while another ascribes a synsedimentary origin to the Cu, Pb–Zn and FeS deposits (Lindqvist 1969; Verwoerd and Cleghorn 1975; Both 1990; Toteff 1999).

Verwoerd and Cleghorn (1975) proposed copper at the Kanmantoo mine was synsedimentary in origin but was remobilised during subsequent tectonic activity. Synsedimentary models for base metal mineralisation eventually became the favoured ones and formed the basis for exploration programs in following decades, focusing largely on the Talisker and Tapanappa formations. Companies such as BHP, Aberfoyle Resources Ltd, Northern Mining Corp., and particularly CRA Exploration Pty Ltd (CRAE; CRA stands for Conzinc – Rio Tinto Australia, a consortium formed between Broken Hill Consolidated, Zinc Corp. and UK-based Rio Tinto) were granted mineral exploration tenements along the Kanmantoo Trough. Initial efforts were soon vindicated with the CRAE discovery of a small, low-grade, stratabound Pb–Zn resource at Mount Torrens hosted by Talisker Formation (700,000 t at 6.4% Pb, 1.6% Zn, 41 g/t Ag). However, CRAE soon shifted focus to the overlying Tapanappa Formation, which was ‘obviously the locus of significant syngenetic base-metal mineralisation’ (Wills and Cook 1981).

Northern Mining Corp. tested the base metal rich host unit at various places extending from Kanmantoo to Strathalbyn, completing detailed work at Wheal Ellen and Strathalbyn mines. At the latter, undeterred by the unsuccessful Mines Department work 18 years previously, they carried out bedrock geochemical sampling and an IP (induced polarisation) geophysical survey, followed by 6 drillholes. Both the geochemical sampling and the surface geophysical surveys were extended north of historical workings and south, to the Mount Barker railway line passing 100 m away from there, but then went no further in the direction of Angas, even though exposed lode rocks were observed in railway cuttings. Narrow high-grade mineralisation was intersected near the Strathalbyn mine, but Northern Mining Corp. decided that its new data precluded the possibility of there being an economic-size orebody. They noted ‘both pyrite and base metal mineralisation are of undoubted syngenetic origin and have been subjected to remobilisation’ (Northern Mining Corp. NL 1971, p 10).

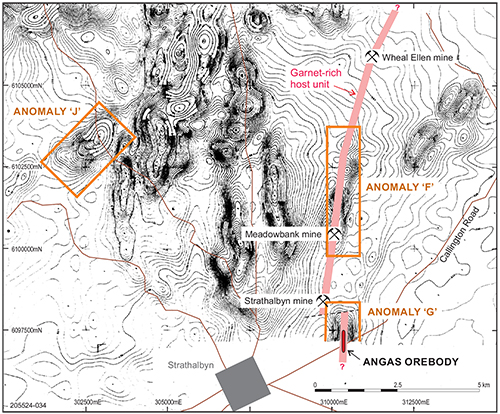

Figure 3 Total magnetic intensity data contours from the airborne magnetic survey carried out by CRA Exploration in late 1979, showing the locations of the 3 identified target anomalies in the Strathalbyn area. Note relationship of anomaly ‘G’ with the Angas orebody. (Garnet host rock is superimposed onto CRA figure.)

CRAE held a series of tenements covering most of the 200 km of exposed Kanmantoo Trough sediments from the Karinya Syncline in the north to Encounter Bay in the south, undertaking extensive airborne geophysical surveys, initially for magnetics and then for electromagnetics (EM). An initial airborne magnetic survey was carried out late in 1979 with a number of anomalies identified for further investigation, 3 of which (anomalies F, G, J) were close to Strathalbyn. CRAE’s data interpretation consultant noted anomaly ‘G’ lay along the southern portion of the Wheal Ellen – Strathalbyn mine trend, with the latter mine at the northern extremity of the anomaly. In fact, anomaly ‘G’ corresponded directly with what we now know to be the Angas deposit (Fig 3).

When it came time to check anomaly ‘G’ on the ground, CRAE reported it lay within an area ‘currently undergoing major earthworks development. In consequence no effective exploration can be carried out on this anomaly’ (Bubner 1982, p 4). The earthworks involved construction of new wastewater/effluent lagoons to service the growing population of Strathalbyn. Surprisingly, CRAE geologists did not inspect the site of these earthworks directly overlying an intense aeromagnetic anomaly, thus missing the opportunity to identify its source. The finished wastewater lagoon cuts across the southern extension of the Wheal Ellen – Strathalbyn mine host unit trend and is only 50 m from the unnamed mine discovered by prospectors in 1869, representing the surface lode expression of the Angas deposit. Although one can only speculate, it is highly probable the Engineering & Water Supply Department earthworks exposed recognisable lode rocks with gossan and characteristic mineralogy (andalusite, staurolite, Mn-garnet and gahnite) that can still be seen surrounding the nearby old mine shaft. Hence the Angas deposit was dismissed again, this time by exploration geologists more than 110 years after being abandoned by prospectors.

The following year, in October 1983, CRAE completed a combined (sensor platform) airborne induced pulse transient (INPUT) EM and magnetic survey (the ‘Mount Barker’ survey) covering 467 km2 of the southern Kanmantoo Trough at 400 m flight line spacing. Many INPUT EM anomaly zones correlated well with magnetic anomalies, so the survey datasets became a useful mapping tool, defining broad fold structures and large linear trends. Analysis of the INPUT EM data by Geoterrex Pty Ltd identified 42 anomalous conductive zones, sorted into 3 levels of priority: priority 1 – most likely a bedrock origin, indicating a moderate to highly conductive source; priority 2 – also bedrock origin but without a highly conductive source; and priority 3 – targets almost certainly of surficial or cultural origin, but for which there existed a degree of uncertainty (Nader 1984).

INPUT EM anomaly MB-21, with a strike length of 950 m, corresponded with aeromagnetic anomaly ‘G’ and therefore with the Angas orebody, but unfortunately it was placed into the priority 3 category. It is defined across 2 flight lines as sharp, well-defined conductive responses with medium to large amplitudes. Geoterrex noted the response on the first line coincided with a shed and powerlines, and therefore was most likely due to these cultural features. Anomalous readings obtained on the second flight line, however, showed no obvious cultural sources. Geoterrex recommended that priority 3 anomalies thought to be associated with cultural sources could be ‘upgraded to priority 1 if ground investigations prove no man-made source is evident’ and recommended all inferred cultural anomalies be inspected to confirm the source (Nader 1984).

As with aerial magnetic anomaly ‘G’, there is no record that INPUT EM anomaly MB-21 was followed up in the field. Ironically, the main Strathalbyn–Callington road, just over 100 m south of the Meadowbank Swamp, passes directly through both anomalies, and also through the eventual discovery outcrop, which is clearly exposed in a road cutting only 2 km from Strathalbyn. Its recognition by another company 10 years later finally led to drill testing of the Angas ore body. Perhaps it is possible CRAE geologists had driven over this very outcrop on their way to town for lunch, without recognising its significance!

Only 2 years after CRAE missed its chance of finding Angas by neglecting to ground check aeromagnetic anomaly ‘G’, it was again missed by not ground-truthing the source of INPUT EM anomaly MB-21. Five other INPUT EM anomalies were selected instead as priority targets and tested with surface geochemical sampling, ground EM and magnetics surveys and, in one instance, with limited drilling. No success came of this, and CRAE soon afterwards stopped its exploration activities in the Strathalbyn district.

Discovery (post-1990)

Figure 4 Discovery outcrop (arrowed) along the Strathalbyn to Callington road, 2.5 km east from Strathalbyn, looking east. Host unit outcrops as reddish-brown, gossanous metasediment with Mn-garnet, andalusite ± gahnite.

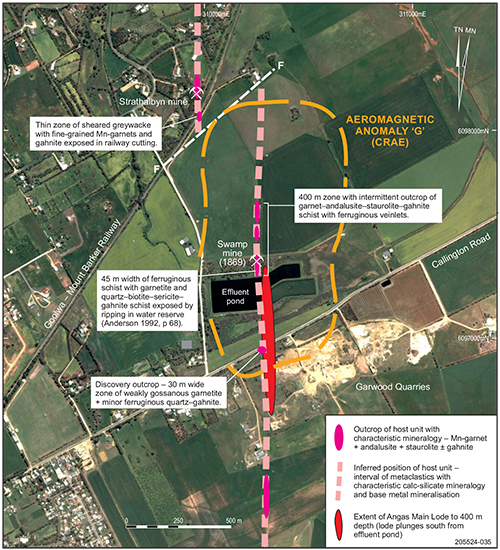

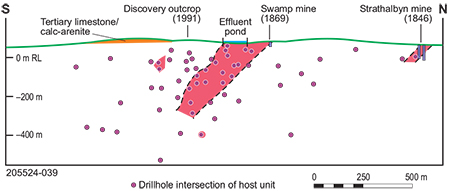

Aberfoyle Resources next took up the challenge of exploring for Middle Cambrian synsedimentary base metal mineralisation within the Kanmantoo Trough, acquiring Exploration Licence (EL) 1706 on the recommendation of geologist Steve Toteff. They undertook detailed reconnaissance field geological mapping between Kanmantoo and Strathalbyn, finding laminated garnet-rich exhalatives (coticules) ± gahnite to be more widespread than previously reported (Anderson 1993). Aberfoyle traced these vector rocks south from Kanmantoo to Strathalbyn mine, but unlike previous workers they did not assume the zone stopped there, but rather predicted it would continue further south. For taking this view they were rewarded in December 1991 when Toteff discovered a 30 m wide zone of weakly gossanous, garnet and gahnite-rich outcrop, the ‘discovery outcrop’ (Figs 4, 5), in a shallow cutting along the southern edge of the Strathalbyn to Callington road (Anderson 1992).

Backtracking to the north from this cutting, Toteff mapped a 45 m wide float zone of gossan and quartz–gahnite–garnet rock spread along the northern side of the Strathalbyn effluent lagoon, next culminating in his rediscovery of the ‘Swamp mine’ shaft, dug in 1869 when the lagoon was still the Meadowbank Swamp (Fig 5). This undoubtedly would have occurred 9 years earlier if CRAE had managed to field check aeromagnetic anomaly ‘G’. From the old mine shaft, the host unit was followed 300 m northwards, upslope, through a paddock used for wheat production before disappearing beneath Cenozoic ferricrete.

To the south of the discovery outcrop, the gossanous gahnite–garnet-rich assemblage and host Kanmantoo Group metasediments are unconformably overlain by flat-lying bioclastic limestone of the Miocene Mannum Formation, before both disappear beneath Recent alluvial sediments of the Angas River floodplain. Anomalous values for Pb, Zn, Ag, Au and Hg obtained by Aberfoyle from soil sampling and bedrock RAB auger geochemical drilling done subsequently in 1991 outlined a north–south-trending zone almost 2 km in length.

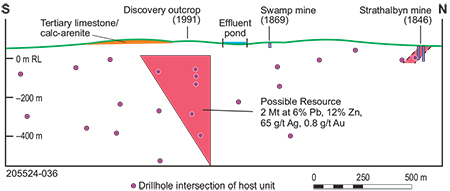

Figure 6 Aberfoyle Resources Ltd’s modelling of north-dipping, high-grade sulfide mineralisation at Angas, adapted from Toteff and Painter (1994).

Aberfoyle commenced deep drill testing in mid-1992, with a combined diamond–percussion drilling program. Initial drillholes encountered broad base metal mineralised intervals of 0.2–1.5% Pb + Zn, and made several narrow high-grade intersections. Drilling soon became focused on the central portion of the surface anomalous zone, between the effluent lagoon and Garwood Quarry. Drilling continued intermittently until 1994, by which time 17 diamond drillholes and 7 percussion holes totalling 9,766 m had been completed. Using the surface drillhole data, Aberfoyle modelled a narrow, steeply north-dipping body of high-grade mineralisation (Fig 6), approximately triangular in outline with a ‘pre-resource potential’ of 2.1 Mt at 10.7% Zn, 4.9% Pb, 60 g/t Ag and 1.0 g/t Au (Toteff and Painter 1994) and an inferred resource of 1 Mt at 10% Zn, 4% Pb, 60 g/t Ag and 1 g/t Au (Bampton 2003).

Encouraged with the announcement of Aberfoyle’s discovery, North Mining Ltd farmed into EL 1706 and managed a joint venture for 2 years from October 1994. They did not, however, undertake additional work on the Angas prospect, regarding it as having insufficient potential to reach their target commercial deposit size – i.e. Angas was dismissed as being too small. It was, however, used as a template for their objective of finding larger deposits in the surrounding tenements. Thirty-two geophysical targets were evaluated with ground magnetic surveys, soil/rock geochemical sampling and RAB/AC bedrock drilling, without proceeding further in that time.

Subsequent to North Mining Ltd’s exit from the project, Terramin (as Playford Resources NL) formed the Fleurieu Exploration Joint Venture with Aberfoyle in July 1997 and became project manager. The following year Aberfoyle was taken over by Western Metals Ltd (subsequently Western Metals Copper Ltd). Exploration focus returned to the Angas deposit, with Terramin committed to define a small but high-grade mineable resource. An additional 12 drillholes were completed, meeting with varied success including the most significant intersection made up until that time, a wide interval of massive sphalerite–galena mineralisation in drillhole AN029 – 14.4 m at 22% Zn, 4.8% Pb. 33 g/t Ag and 0.5 g/t Au.

Figure 7 Longitudinal view of host unit with modelled resource ore lenses of Rankine Lode, looking west. Adapted from Angas Scoping Study (Wallis 2000).

Incorporating its drilling data with ground (magnetic, gravity) and downhole (DHEM) geophysics, Terramin’s lode structure modelling used a near-vertical to steep southerly plunge for ore shoots (Fig 7), in contrast to Aberfoyle’s north-plunging interpretation (Bampton 2003). In 2001 Maptek Pty Ltd completed an updated resource estimate, advancing the resource from Inferred-only to Inferred + Indicated status, JORC (1999) compliant. A Zn-equivalent value, based on market price for Zn, Pb, Ag and Au at the time, was used. The updated resource of 930,000 t at 20% Zn equiv. represented a similar tonnage to Aberfoyle’s 1994 resource, but with an approximately 50% increase in grade (Aberfoyle Resources 1994; Johnson and Sullivan 2001).

Unfortunately for Angas, the 2001 zinc price was at a 10-year low and did not improve until 2003, making it difficult to raise funds to advance the project. As the price of zinc and other metals commenced an upward trend in 2003 Terramin proposed to seek funds through a public offering. The company listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) on 23 December 2003.

So, in the early 21st century the fortunes of Angas were improving with Terramin hitting the right combination of rising metal prices and abundant capital. Soon after listing on the ASX, drilling of the Angas prospect recommenced in early 2004, aiming to expand the size of the known 930,000 t resource. In addition, as metal prices continued to rise, Terramin acquired new base metal projects in Australia and overseas. An in-house review of Angas drilling data in mid-2004, using the steep-plunging model of ore shoots, indicated the aim of at least doubling the resource size might not be achievable, and so work at Angas should be paused while advancing work on the new projects. Angas was on the verge of being dismissed yet again.

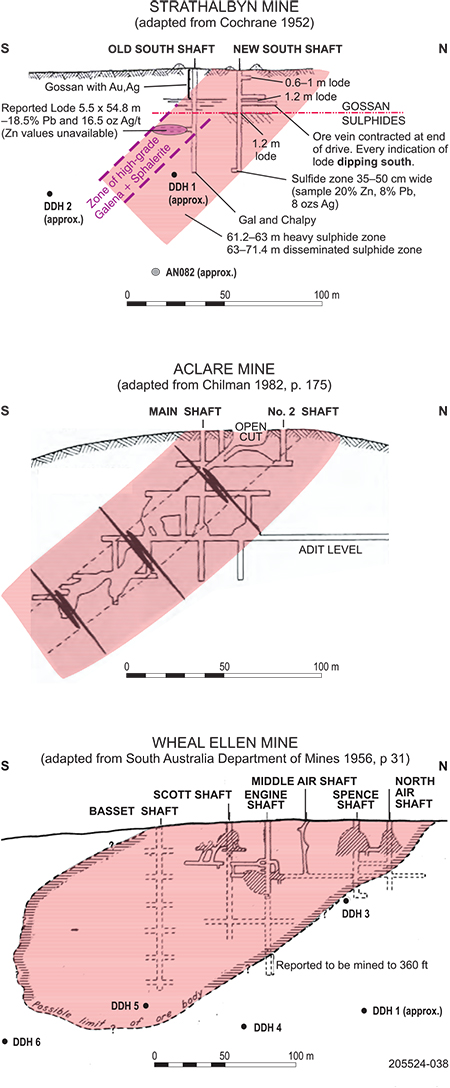

Figure 8 Longitudinal views of historic mines near Strathalbyn (looking west), modified from old government reports, showing the moderately south-plunging control to mineralisation (Ogierman 2004).

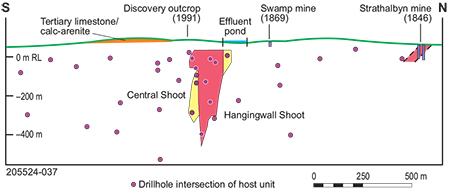

Before a final decision was made, it was recommended to conduct a review of all available data. The South Australian Resources Information Gateway (SARIG) online portal enabled Terramin to gain access to historical reports from the 19th and 20th centuries about mines in the Kanmantoo district. These reports highlighted a recurring theme of moderately south-plunging ore shoots in mines such as Wheal Ellen, Aclare (Fig 8) and even the Brukunga pyrite mine. This prompted a revision of the old Strathalbyn mine, and it became apparent this too had south-plunging shoots of high-grade ore, not recognised when drill tested in the 1950s and 1970s (Fig 7). A regional structural control to high-grade mineralisation was apparent, creating lodes parallel to shallow south-plunging fold axes of dominant D2 fold structures in the Strathalbyn district.

Terramin’s reappraisal of Angas diamond drill core structural data, particularly for parasitic folds and extensional features such as boudins, confirmed that a south-plunging orientation was important in modifying and more significantly, in upgrading the concentration of sulfide mineralisation. This led to a new understanding of the Angas deposit, suggesting that its stratabound base metal mineralisation was structurally modified during deformation, with sulfides becoming remobilised into zones of low-strain along boudin necks, parallel to D2 south-plunging axes (Ogierman 2004).

The new orebody model proposed that high-grade shoots plunge moderately to the south instead of steeply south or at near-vertical orientations, as previous workers had suggested (Ogierman 2004). A new resource estimation was undertaken, independently confirming the ore body architecture with 3D modelling. The bulk of mineralisation was in a thin planar body (the Rankine Shoot), plunging 450 to the south and dipping 700 east (Fig 9). The resource was significantly increased from 930,000 t at the start of 2004 to 2.78 Mt at 8.9% Zn, 3.3% Pb and 42 g/t Ag by the end of the year, allowing the company to proceed to prefeasibility stage (Terramin 2005).

Figure 9 Longitudinal view of Terramin Resources’ new interpretation of moderate south-dipping orientation of the main Rankin Shoot (Ogierman 2004).

Drilling at Angas recommenced in early 2005, focusing on infill and strike-extension targets. By the end of 2005, the resource had increased again to 3.04 Mt within JORC (2004) guidelines (Larsen 2005). The good luck continued with zinc continuing its strong price rise, reaching a historic peak of US$4,442/t in November 2006, a greater that 400% increase since Terramin had listed on the ASX only 3 years prior. With the support of an increasing base metal price, the Terramin Board agreed to progress development of an underground mining project at Angas to extract with a Probable Ore Reserve of 2.34 Mt at 8.1% Zn, 3.1% Pb, 0.3% Cu, 33 g/t Ag and 0.5 g/t Au for a projected mine life of 7 years.

Thus at the beginning of the 21st century, more than 130 years after it was discovered in the 19th century and then missed or dismissed by prospectors and mining companies in the 20th century, it transpired that the potential of the Angas deposit was finally recognised. July 2008 saw the commissioning of the Angas zinc mine, with the first delivery of produced lead concentrate trucked to the Port Pirie Smelter in the same month, and a first consignment of zinc concentrate shipped to South Korea 2 months later.

Although development of the mine at Angas was finally achieved via a combination of new geological thinking and rapidly rising metal prices, operations were immediately placed under strain as financial markets and metal prices reeled from the global financial crisis which gripped world economies in 2007–2008. Just as quickly as the price of lead and zinc had risen so high, it fell, to lows of US$1,115 and US$1,075 per tonne, respectively, in the first week of 2009. Fortunately, markets recovered during 2009 and prices of both metals doubled by the end of the year, but never again reached the peaks of late 2006 for the duration of mining. The original 7-year mine life, proposed when metal prices were high, could not be sustained as prices dropped. The mine had operated at a production rate of 0.4 Mt of ore per annum from 2008, but mining was stopped and the project was placed on care and maintenance late in 2013.

Conclusion

Although the Angas Project only involved a moderate-size, high-grade base metal deposit which was mined over a relatively short timeframe, there are several lessons which can be learned from its discovery and development. Exploration work which led to the final recognition and definition of the orebody is patently a story of the 3 ‘P’s– perseverance, perspective and price.

Ultimately Angas represents a geological success story, albeit a lengthy one, covering nearly 4 decades from the day when CRAE first identified potential for sediment-hosted base metal mineralisation in the Kanmantoo Trough. Although CRAE did not ultimately garner success by working within its corporate parameters, it inspired other exploration companies who soon followed and refined the geological model, focusing on a prospective horizon with characteristic calc-silicate mineralogy, so extending the zone southwards, along strike from historical mines, leading to the ‘discovery outcrop’ in 1991. Success was still not assured at this stage, with the project facing changing corporate leadership and associated changing corporate objectives, and then being challenged by falling global metal prices. Even at the start of the 21st century when it seemed these obstacles had been overcome with the floating of Terramin on the ASX, much perseverance was still required, as well as a crucial change in perspective of the geological model gained with the help of key historical data newly accessible on the SARIG online portal.

Companies and individuals now have 24/7 access to a vast array of valuable South Australian geoscientific data online, from historical mining to present day terrain-scale geochemical and geophysical surveys. Notwithstanding the use of ever advancing methods of processing and presenting data, including artificial intelligence, there is still a need for critical interpretation of the data and sometimes, for a reinterpretation from a different perspective.

Perhaps the most important lesson to be gained from the discovery of Angas is the realisation of why it took nearly 150 years from when outcropping gossan adjacent to Meadowbank Swamp was first tested by prospectors until opening of the underground mine by Terramin and production of copper and zinc concentrate in 2008. If this can happen in terrain with outcropping geology, only 50 km from a major population centre of 1+ million people and with the discovery outcrop exposed in a major regional road, what does it imply about the mineral prospectivity in the remainder of the state where outcrop is poor or non-existent, population density is also very low and exploration data is often restricted to large-scale, open-source geophysical surveys?

Acknowledgements

Richard Lilly (University of Adelaide) and Mark Griffiths (Geological Survey of South Australia) are thanked for their reviews of this paper. Prof Ross Both, Prof Paul Spry, David Paterson (former Director of Terramin Australia Ltd) and David Larsen (former Exploration Manager of Terramin) are also thanked for their input and comments.

References

Belperio A, Preiss W, Fairclough M, Gatehouse CG, Gum J, Hough J and Burtt A 1998. Tectonic and metallogenic framework of the Cambrian Stansbury Basin - Kanmantoo Trough, South Australia. AGSO Journal of Australian Geology & Geophysics 17(3):183–200.

Both RA 1990. Kanmantoo Trough - geology and mineral deposits. In Hughes FE ed, Geology of the mineral deposits of Australia and Papua New Guinea. The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Melbourne, pp 1195–1203.

Flöttmann T, James P, Rogers J and Johnson T 1994. Early Palaeozoic foreland thrusting and basin reactivation at the Palaeo-Pacific margin of the southeastern Australian Precambrian Craton: a reappraisal of the structural evolution of the Southern Adelaide Fold-Thrust Belt. Tectonophysics 234(1–2):95–116. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(94)90206-2.

Foden J, Elburg MA, Turner SP, Sandiford M, O’Callaghan J and Mitchell S 2002. Granite production in the Delamerian Orogen, South Australia. Journal of the Geological Society, London 159:557–575. doi:10.1144/0016-764901-099.

Jago JB, Gum JC, Burtt AC and Haines PW 2003. Stratigraphy of the Kanmantoo Group: a critical element of the Adelaide Fold Belt and Palaeo-Pacific plate margin, Eastern Gondwana. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 50(3):343–363. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0952.2003.00997.x.

Johnson KR and Sullivan S 2001. Angas prospect, revised geological resource assessment. Unpublished Maptek Pty Ltd report to Terramin Australia, May 2001.

Laing WP 1998. Architecture of the Angas Pb+Zn deposit: 2nd report. Unpublished report to Terramin (Australia) NL, 14 September 1998.

Larsen D 2005. Angas Resource update – 7 November 2005. Internal report to Terramin Australia Ltd, November 2005.

Lindqvist WFL 1969. Geology and metamorphic history of the Kanmantoo copper deposit, South Australia. PhD thesis, University of London.

Offler R and Fleming PD 1968. A synthesis of folding and metamorphism in the Mt Lofty Ranges, South Australia. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia 15(2):245–266. doi:10.1080/00167616808728697.

Ogierman JA 2004. An analysis of sulphide mineralisation styles and their relationship to the structural environment in the Angas Deposit, Strathalbyn, South Australia. Unpublished internal report to Terramin Australia Limited, September 2004.

Parker AJ 1986. Tectonic development and metallogeny of the Kanmantoo Trough in South Australia. Ore Geology Reviews 1(2–4):203–212. doi:10.1016/0169-1368(86)90009-0.

Pollock MV, Spry PG, Tott KA, Koenig A, Both R and Ogierman J 2018. The origin of the sediment-hosted Kanmantoo Cu-Au deposit, South Australia: mineralogical considerations. Ore Geology Reviews 95:94–117. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2018.02.017.

Pontifex I 1992. Mineralogical report 6224. Unpublished report for Terramin Australia Ltd.

Rosenbaum G 2018. The Tasmanides: Phanerozoic tectonic evolution of eastern Australia. Annual Review Earth and Planetary Science Letters 46(1):291–325. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-082517-010146.

Spry PG 1976. Base metal mineralization in the Kanmantoo Group, South Australia, the South Hill, Bremer and Wheal Ellen areas. BSc Hons thesis, University of Adelaide.

Terramin Australia Ltd 2005. Angas pre-feasibility study, April 2005. Unpublished internal report.

Thomson BP 1975. Kanmantoo Trough-regional geology and comments on mineralization. In Knight CL ed, Economic Geology of Australia and Papua New Guinea, Vol. 1. Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Melbourne, pp 555–560.

Tott KA, Spry PG, Pollock MV, Koenig A, Both RA and Ogierman J 2019. Ferromagnesian silicates and oxides as vectors to metamorphosed sediment-hosted Pb-Zn-Ag-(Cu-Au) deposits in the Cambrian Kanmantoo Group, South Australia. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 200: 112–138. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2019.01.015.

Verwoerd PJ and Cleghorn JH 1975. Kanmantoo copper orebody. In Knight CL ed, Economic Geology of Australia and Papua New Guinea, Vol. 1. Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Melbourne, pp 560–565.