Tin

Tin (Sn) has been used and traded by man for more than 5000 years, it has been found in the tombs of ancient Egyptians, and was exported to Europe from Cornwall, England, during the Roman period. The principal ore of tin is cassiterite (SnO2) but some tin is produced from sulphide minerals such as stannite (Cu2FeSnS4).

Tin is a silver-white metal of low melting point, is highly ductile and malleable, resistant to corrosion and fatigue, has the ability to alloy with other metals, is non-toxic and is easily recycled. At temperatures below 13°C it can change to an amorphous greyish powder known as grey tin and, because of the resultant mottled appearance of tin objects, the action is commonly called tin disease.

Tin has many important uses throughout the world, particularly as tinplate which is used as a protective coating on steel cans for food packaging. It is used in the production of the common alloys bronze (tin and copper), solder (tin and lead) and type metal (tin, lead and antimony). It is also used as an alloy with titanium in the aerospace industry. Inorganic compounds of tin are used in ceramics and glazes while organic compounds of tin are used in plastics, wood preservatives, pesticides and fire retardants.

The annual world mine production of tin is ~230 000 t (2013), with the major producers being China (41%), Indonesia (20%), Peru (15.5%), Brazil (5.5%), Bolivia (5%) and Australia (3.8%). Australia’s annual mine production was ~18 000 t, with most of the economic resources at the Renison Bell deposit in Tasmania which supports one of the world’s largest underground tin mines. Greenbushes in Western Australia is also an important producer of tin along with tantalum. A significant amount of tin is recycled; the steel can recycling rate is 50–60% in the western world.

Tungsten

Tungsten and its alloys are amongst the hardest of all metals. And tungsten itself has the highest melting point of pure metals. This combination of hardness and high melting point makes it desirable for many industrial applications. The major use of tungsten is with cemented carbides. Tungsten carbide is used for cutting in wear-resistant materials. Tungsten alloys are used in electrodes, filaments, wires and components for electrical heating, lighting and welding applications. Tungsten has chemical applications including catalysts, and pigment in paint. Ferrotungsten is used in steel and alloys where hardness and heat resistance are required.

In nature it occurs as wolframite, (Fe,Mg)WO4, and scheelite, CaWO4. Tungsten is usually supplied as a mineral concentrate.

World production of tungsten metal in 2013 was 71,000 tonne, and was dominated by China. Australian production in 2012 was 290 tonne, from mines in WA, Queensland, and Tasmania. World resources of tungsten in 2013 of 3.5 Mtonne tungsten metal are dominated by China, with Australia ranked 2nd with Demonstrated Resources of 391,000 tonne tungsten. 60% of Australian resources are located in WA, with most of that from the O’Callaghans deposit. Other significant resources are found in Queensland, Tasmania, and the Northern Territory.

South Australian deposits

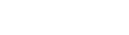

Tin

South Australia’s tin production is insignificant and totals ~2 t of cassiterite concentrate. The major known tin occurrences are on the Gawler Craton where cassiterite was first recorded in 1899 at South Lake. This occurrence was also prospected ~1917 and in the early 1940s. The workings comprise several shafts, the deepest being 16.5 m. There is no recorded production but cassiterite concentrate, probably <2 t, was produced on site. Mineralisation is in quartz veins, up to 1 m wide, within Archaean Kenella Gneiss of the Mulgathing complex. Mineralisation is considered to be sourced from Mesoproterozoic Hiltaba Suite granite.

Cassiterite was first reported at the Mount Mitchell Tin Workings in 1923 at the northern end of the Glenloth Goldfield. Prospecting comprised pits, trenches and shallow shafts to 7.5 m extending for ~800 m along strike. Cassiterite is disseminated in north–south-trending quartz and greisen veins, up to 3 m wide, hosted by Archaean to Palaeoproterozoic Glenloth Granite. The cassiterite and associated gold, monazite, molybdenite and base-metal sulphides are considered to be derived from a shallow Hiltaba Suite batholith. There is no recorded production from the workings.

At Warna Rock Hole, anomalous but erratic tin values have been recorded from quartz–greisen veins within Hiltaba Suite granite.

Significant cassiterite concentrations were discovered in the Curnamona Province in 1980 at Prospect Hill and subsequent exploration has returned drill intersections of up to 3.5% Sn over 6.2 m. Cassiterite with minor chalcopyrite, sphalerite, scheelite, silver and gold is contained within a siliceous, elongated east–west zone of highly deformed Mesoproterozoic acid volcanics at the northern end of the Mount Babbage Inlier.

Exploration drilling in 2013 identified significant tin skarn-type mineralisation at the Zealous and Ultima Dam West prospects in the northern Eyre Peninsula.

Tungsten

On the Spilsby Islands (Langton Island), minor production of 155 kg of wolfram ore was recorded from molybdenum-tungsten vein mineralisation associated with a Mesoproterozoic granite intrusion.

In the historic Callawonga Creek alluvial goldfield, scheelite (CaWO4), and ferberite (FeWO4) as disseminations, shoots, and masses in host quartz-tourmaline pegmatoid veins was recovered from the hard rock mine of Queen Mary, minor also from the mine Gaba Tepe from 1915-18. Total production of tungsten metal equivalent was in the order of 2.7 tonne.

Minor prospects for polymetallic mineralisation including tungsten (as scheelite), have been identified by mapping and drilling in the northern Flinders range at the Giants Head, Tourmaline Hill, and Eastern Schist Belt prospects.

At the Moonbi prospect, tungsten mineralisation has been penetrated in drillholes testing the margins of a bullseye magnetic anomaly in the western Mulgathing Complex. Moonbi may possibly represent skarn type mineralisation. Best intercepts include 2m at 1.27% WO3 in hole MRC005.

Additional Reading

Daly, S.J., 1993. Earea Dam Goldfield (Mesoproterozoic). In: Drexel, J.F., Preiss, W.V. and Parker, A.J. (Eds), The geology of South Australia. Vol. 1, The Precambrian. South Australia. Geological Survey. Bulletin, 54:138.

Morris, B.J., 1980. Rock chip sampling of Mount Mitchell tin workings. Mineral Resources Review, South Australia, 152:23-27.

Morris, B.J., 1981. Tin prospect near Warna Rock hole — rock chip sampling. Mineral Resources Review, South Australia, 153:69-73.

Teale, G.S., 1993. Geology of the Mount Painter and Mount Babbage Inliers (Mesoproterozoic). In: Drexel, J.F., Preiss, W.V. and Parker, A.J. (Eds), The geology of South Australia. Vol. 1, The Precambrian. South Australia. Geological Survey. Bulletin, 54:149-156.