Regolith can be described as the entire unconsolidated or secondarily re-cemented cover that overlies more coherent bedrock. Regolith includes fractured and weathered bedrock, saprolites, soils, organic accumulations, volcanic material, glacial deposits, colluvium, alluvium, evaporitic sediments, aeolian deposits and ground water (adapted from Eggleton 2001, p. 101), or in a shorter form as ‘everything between fresh rock and fresh air’ (Eggleton 2001, p. 101). It has been formed by weathering and erosion of the older material, and by transport and/or deposition of younger overlying materials.

Regolith is continuously formed and modified, and what we observe in today’s landscape is a result of past, present and ongoing events. Regolith is an integrated expression of geology, climate, groundwater, topography, geomorphic processes and landscape evolution and has a very close empirical relationship with landforms, both present-day and past. Landforms are themselves a reflection of climate, geology and predominantly near-surface geomorphic processes (Craig 2005).

South Australia has a wide variety and diversity of regolith materials and landforms. Over 75% of the State is covered by transported regolith material (Krapf et al. 2012) and is therefore a major challenge that mineral exploration faces in many parts of South Australia in exploring efficiently and effectively through this extensive and thick cover. In addition, regolith itself hosts important resources.

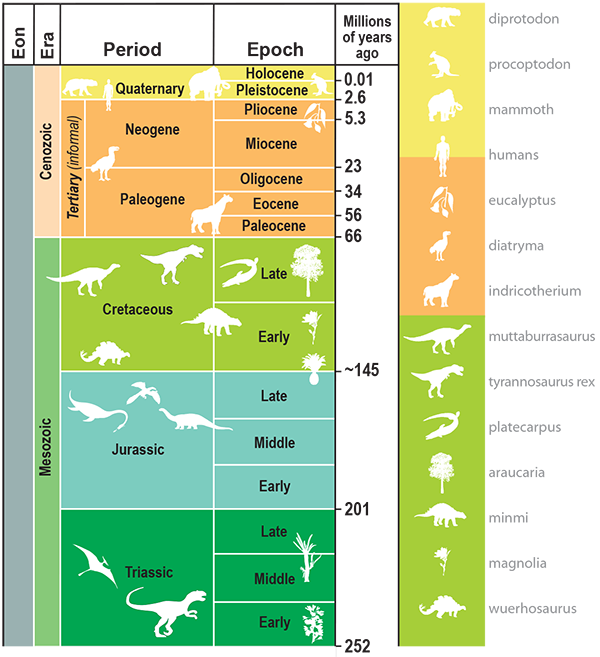

Regolith profiles at Mount Gunson Mine. (Photo 045300)

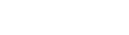

Age of major events

Preservation potential of regolith, already poor due to its formation close to the earth’s surface, decreases generally with time, thus only fortuitous and major culminations of regolith development will be retained in the older rock record.

The formation of regolith is closely related to weathering driven dominantly by changes in climate. This resulted in the widespread occurrence of extensively weathered rocks throughout South Australia, commonly reaching depths of 10 to 100 m.

- Extensive deep weathering occurred prior to the Middle Eocene and may be as old as early Mesozoic.

- Deep weathering after the Late Eocene – Early Oligocene appears to be dominantly related to the formation of duricrusts (Benbow et al. 1995) and paleodrainage and ancient coastal barrier systems (Hou et al. 2012).

- Duricrusts formed semi-continuously from Early Paleocene to Pleistocene and cap a variety of paleosurfaces of different ages and origins.

- Major silcrete and minor ferricrete formation occurred in the Paleocene to Early Eocene, Late Eocene and Late Miocene to Early Pliocene.

- Increased aridity and persistent strong winds during the Pleistocene caused the development of extensive dunefields like the Simpson and Great Victoria deserts. During this period a variable influx of aeolian carbonate dust, sourced from the exposed continental shelf during sea level low stands, lead to extensive calcrete and soil formation throughout South Australia.

Geological timescale (download PDF).

Prospective commodities

Regolith hosted REE deposits globally including, ion adsorption clay.

Deposits (eg Koppamurra), alluvial and placer deposits; Ni, Co, Au, PGE, Fe, U, heavy mineral sands (eg ilmenite, chromite, magnetite, zircon, rutile, leucoxene, garnet), precious stones (eg opal, chrysoprase, sapphire, diamond), extractive minerals – calcrete, gypsum, phosphate, salt, kaolin, halloysite, palygorskite, silica sand, peat, industrial clay, groundwater, and construction materials.

Major exploration tools

- Regolith sampling: calcrete, soil, transported regolith (sediments), lag, siliceous material, ferruginous material, in-situ regolith (bedrock/saprock/saprolite)

- Remote sensing (DEM, multispectral and hyperspectral data)

- Geophysical data (radiometrics, gravity, AEM, TEM, shallow seismic, GPR)

- Biogeochemistry sampling

- Groundwater sampling

- Paleochannel and paleolandform mapping

- Paleodrainage and Cenozoic coastal barriers map 2nd edition

The updated version includes revised sediment boundaries based on newly acquired datasets; a modified approach to paleodrainage mapping following industry feedback (eg airborne electromagnetic (AEM) interpretation workshops); new data from mineral exploration activity (eg drilling data); and geological sections illustrating sediment and bedrock relationships. - The 2M Paleodrainage and Cenozoic coastal barriers GIS dataset is available from SARIG via the Geology - palaeodrainage systems layer group.

- Paleodrainage and Cenozoic coastal barriers map 2nd edition

- Regolith mapping

- The 1:2 000 000 regolith map of South Australia consists of three main data components — regolith materials and landforms, regolith material induration (ferruginous, calcareous, siliceous, gypsiferous, mixed and undifferentiated), and surface lag. The 2M regolith GIS dataset is available from SARIG via the Geology - regolith layer group.

- Regolith material of the Greater Tarcoola Area of the Central Gawler Region (MALBOOMA, TARCOOLA and KINGOONYA 1:100 000 map sheets)

- Regolith map of Coompana region

- Regolith map of the Southern Gawler Range Volcanics

- Relevant regolith layers in SARIG

Summary geology

Regolith materials can be divided into five broad types — transported, in situ, indurated, lags, and soils. Observing and mapping these broad types of regolith materials, along with landscape setting, can assist in creating regolith-landform relationship models to aid in understanding and characterising regolith and cover.

Types of regolith

Transported sediments are the most generalised transported regolith material class, as it refers to regolith material that is either of mixed or unknown origin but has experienced transport, especially in areas of transitional or spatially complex regolith landform regimes. They are often overprinted by calcareous and/or siliceous induration or they represent the source sediments of an overlying lag.

In situ regolith accounts for 25% of South Australia’s regolith by area. There is hardly any outcropping bedrock in South Australia that hasn’t experienced some degree of weathering. Weathering intensity can vary dramatically over short distances within an outcrop area.

Examples of transported and in-situ regolith in South Australia:

Aeolian sediments are the dominant regolith material in South Australia, covering more than 43% of the State. Aeolian landforms such as dunefields and sandplains are widely preserved in today’s landscape, and form extensive parts of the Great Victoria, Tirari, and Pedirka-Simpson-Strzelecki deserts. Coastal dunes and foredunes are also included in this regolith unit.

Colluvial sediments are widespread along range fronts, slopes and rises, and on depositional and erosional plains. Examples of colluvial sediments would include the rocky slopes to plains from Brachina Gorge to Parachilna, and the footslopes of Wilpena Pound. They are variably thick and bedrock-masking heterogeneous deposits of variable grain size. They are typically coarse and angular on upper slopes where they dominantly represent debris flow deposits (Eggleton 2001). Downslope they decrease in grain size and transition into sheet flow deposits.

Alluvial sediments occur mainly along rivers and creeks, with the Murray, Cooper, Warburton, Macumba and Neales rivers accounting for the largest river systems in the State. Most of the river systems in South Australia are ephemeral and experience discharge/flooding only on an irregular basis.

Lacustrine sediments and playa beach sediments are situated along the shores of the large inland lakes and playas (eg Blanche, Callabonna, Eyre, Frome, Gairdner, Harris and Torrens lakes) and also include prominent remnants of Pleistocene beach ridges near Lake Eyre South.

Sheet flow deposits are a subclass of colluvial sediments associated with lower slopes, and generally displaying a distinct contour banding/tiger bush/striping surface pattern. Examples include the Paralana High Plains to the east of Paralana Hot Springs and Mt Painter in the northern Flinders Ranges, and the vast quartz-covered plains south of Innamincka in the Cooper Basin. This surface expression is due to banded mosaic vegetation patterns separated by bare ground that run roughly parallel to contour lines of equal elevation, formed on gently sloping plains (Wakelin-King 1999).

Coastal sediments occur along the marine coastal zone of South Australia and include coastal barrier, back barrier lagoon, shoreface, tidal and delta deposits.

Relatively young volcanic material is restricted to the Quaternary basaltic lava and ash deposits of the Mount Gambier and Mount Burr groups in the Lower South-East of the State. Several cones, domes and maars that punctuate today’s landscape characterise the volcanism in this area (Sheard 1993).

Spring deposits are associated with the mound springs of the southern margin of the Great Artesian Basin. These springs can arise from a mound, rock fracture or a seep, and form low hills of limestone and gypsiferous, calcareous and carbonaceous/organic silt surrounded by wetlands around their base (Habermehl 1982; Sheard and Smith 1993).

Variably weathered bedrock can be found in many areas of the State and occurs in all geological provinces, with extensive exposures of bedrock mainly in the Flinders, Willouran and Mount Lofty Ranges, Gawler Ranges, Peake and Denison Ranges, Musgrave Ranges and the tablelands of the Eromanga Basin.

Induration

Induration of regolith material (both in-situ and/or transported) has and is still occurring as part of South Australia’s weathering history, mainly by the introduction and precipitation of silica, iron oxides, carbonates and sulphate (dominantly gypsum). The indurated material is generally present as distinctive cemented horizons (termed duricrust and hardpan/pan), which increase the substrate’s resistance to weathering and erosion. Hence the indurated regolith material is often preserved through topographic inversion as profiles capping topographic highs in the modern day landscape.

Lag

Surface lags are common and widespread in many parts of South Australia - eg the Stony Desert and the Moon Plain northeast of Coober Pedy.

Soil/Paleosol

Soils are common and widespread across South Australia but are most thickly developed in the south and southeastern part of the State or in areas of high rainfall and biological activity. Paleosols are relatively common across South Australia but are discontinuous, relict and tend to be incomplete.

References

Benbow MC, Callen RA, Bourman RP and Alley NF 1995. Deep weathering, ferricrete and silcrete. In Drexel JF and Preiss WV eds, The geology of South Australia. Volume 2, The Phanerozoic. Department of Primary Industries Resources South Australia, Adelaide. Bulletin 54:201-207

Craig MA 2005. Regolith-landform mapping, the path to best practice. In Anand RR and de Broeckert R, Regolith landscape evolution across Australia: A compilation of regolith landscape case studies with regolith landscape evolution models. CRC LEME, Perth, 354.

Eggleton RA (editor) 2001. The regolith glossary: surficial geology, soils and landscapes. CRCLEME, Canberra, ACT, 144.

Hou B, Fabris AJ, Michaelsen BH, Katona LF, Keeling JL, Stoian L, Wilson TC, Fairclough MC, Cowley WM and Zang W (compilers) 2012. Palaeodrainage and Cenozoic coastal barriers of South Australia. Digital Geological Map of South Australia, 1:2 000 000 Series (2nd Edition). Department for Manufacturing, Innovation, Trade, Resources and Energy, South Australia, Adelaide.

Krapf CBE, Irvine JA and Cowley WM 2012. Compilation of the 1:2 000 000 State Regolith Map of South Australia – a summary, Report Book 2012/00016. Department for Manufacturing, Innovation, Trade, Resources and Energy, South Australia, Adelaide.

Krapf CBE and Sheard MJ 2018. Regolith hand specimen atlas for South Australia, Report Book 2018/00001. Department of the Premier and Cabinet, South Australia, Adelaide.

Sheard MJ 1993. Quaternary volcanic activity and volcanic hazards. In Drexel JF and Preiss WV eds, The geology of South Australia. Volume 2, The Phanerozoic. Department of Primary Industries Resources South Australia, Adelaide. Bulletin 54:264-268

Sheard MJ and Smith PC 1993. Karst and mound spring deposits. In Drexel JF and Preiss WV eds, The geology of South Australia. Volume 2, The Phanerozoic. Department of Primary Industries Resources South Australia, Adelaide. Bulletin 54:257-261

Sheard MJ, 2007a. Wudinna north area regolith landform maps A and B. South Australia. Geological Survey. Special map 1:20 000 scale, SA_GEOLOGY/geodetail, preliminary digital map (June 2007). PIRSA Spatial Information, Adelaide.

Sheard MJ, 2007b. Regolith characterisation as an aid to mineral exploration in the Wudinna North Area, Central Gawler Province, South Australia. CRC LEME, Open File Report 232.

Wakelin-King GA 1999. Banded mosaic (‘tiger bush’) and sheetflow plains: a regional mapping approach. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 46:53-60.

Further reading

- A guide for mineral exploration through the regolith in the Curnamona Province, South Australia (CRC LEME Legacy Explorers Guide Series)

- A guide for mineral exploration through the regolith of the central Gawler Craton, South Australia (CRC LEME Legacy Explorers Guide Series)

- Regolith Characterisation as an Aid to Mineral Exploration in the Wudinna North area, central Gawler Province, South Australia. Report Book 2007/00014

- Regolith map of South Australia (1st edition) 2012

- Regolith hand specimen atlas for South Australia. Report Book 2018/00001

- Optically stimulated luminescence dating revealing new insights into the age of major regolith units of the eastern Musgrave Province, South Australia. Report Book 2018/00004

- Proceedings for the 5th Australian Regolith Geoscientists Association Conference, Wallaroo, South Australia. Report Book 2018/00011

- Hydrogeochemical Atlas of South Australia. Report Book 2018/00013

- Coompana Drilling and Geochemistry Workshop, 2018. Extended abstracts. Report Book 2018/00019

- Linking cover and basement rocks in the Central Gawler Craton, South Australia. Report Book 2020/00029

- Regional geochemistry of the Coompana area. Report Book 2018/00036

- Models, geology and exploration of heavy mineral deposits in South Australia. Report Book 2021/00011

- Zircon provenance and sedimentary transport processes. Implications for the late Neogene evolution and heavy mineral deposits of the western Murray Basin, South Australia. Report Book 2022/00003

- Eucla Basin and peripheral paleovalleys. Report Book 2022/00011