Mineral and Energy Resources

Department of the Premier and Cabinet

Download this article as a PDF (1.9 MB); cite as MESA Journal 85, pages 41–45

Remediation overview

Leigh Creek coal mine is a major mine that has played a key role in South Australia’s energy history for over 70 years. Credited with enabling post-war industrialisation, remediating the Leigh Creek coalfields was always going to be a significant undertaking for operator Flinders Power Partnership.

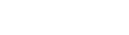

The series of open pits and surrounds cover around 70 km2 (Figs 1, 2). A key site challenge, which is common to remediating most coal mines, is the inherent risk of spontaneous combustion arising from the coal itself and the associated surface water management requirements.

In addition to technical challenges, the site poses a number of significant social considerations: there is a cemetery next to one of the mine pits – on what was the original site of Leigh Creek township – there are Aboriginal heritage sites within the area, and a community preference to maintain the man-made dam for water recreational pursuits and to preserve it as a bird habitat.

The challenge of mine closure has come a long way in recent decades. Environmental managers and regulators can now consider the balance between competing or complementary technical, safety, environmental and social interests, through a strategic planning approach that integrates a suite of methodologies to tackle the risks at hand.

Mine closure planning pulls together a systematic performance-based approach, to identify key risks and management needs, develop ongoing monitoring to track the success of mitigation, and modify approaches over time to adapt to performance needs. For Leigh Creek’s remediation, the public safety and environmental risks were detailed in a comprehensive closure and works plan of more than 4,000 pages, developed over 20 months by Flinders Power.

Figure 2 Aerial view over a section of the Main Series pit. (Courtesy of Flinders Power; photo 416240)

Bringing to life closure related activities, is a team managed by Flinders Power and overseen by South Australian mining and environmental regulators. The team is committed to ensuring the closure plan and works are well managed, consider the potential for post-mining landuse and executed to highest quality standards.

As the mine closure operation reaches its final stages, regulators are pleased with the progress and outcomes delivered by Flinders Power. The vetting process required Flinders Power to submit its Mine Closure Plan, which regulators assessed and collaborated with Flinders Power to identify refinements to the closure methodology. This collaboration will not only improve expected closure outcomes but raise the likelihood of successful relinquishment of the site by Flinders Power to government. The challenge for any operator is closing a site to a suitable standard that the mining lease can be relinquished and the site handed back to government.

Lead regulators have indicated that:

‘While there are many aspects to the Leigh Creek closure and rehabilitation works, the major focus is on reducing the risk of spontaneous combustion which interplays heavily with surface water management, as well as public safety, environmental values, the amenity for the local community and visual amenity for people passing through.

‘At the current rate of progress, Flinders Power expects to wind up much of the on-ground remediation works by mid 2018 and, subject to government assessments and sign off, there will be a period of monitoring – five years likely – to ensure any residual risks continue to be monitored, managed and addressed prior to relinquishment.

‘From the significant works to re-profile the waste rock dumps which will revegetate naturally and blend into the surrounds, we can look forward to a day when tourists may make their way to the attractive post-landuse dam for fishing and water sports.’

Rich history

The former Leigh Creek mine is located 550 km north of Adelaide in a picturesque part of the northern Flinders Ranges.

Long before European settlement, the Aboriginal people referred to the coal deposits in the area as Yulu’s (Kingfisher Man) charcoal. Colonist John Henry Reid came across the coal-bearing shale during the sinking of a railway dam in 1888 in the Leigh Creek area. Leigh Creek coal is considered low-grade sub-bituminous black coal, colloquially called ‘brown coal’. Geologists have dated the coal to the Triassic age (240–200 million years old), occurring as saucer-shaped sedimentary deposits laid down on a pre-Cambrian basement of limestone and shales, and overlain by Quaternary sediments (Flinders Power 2017).

Various early attempts to scale up profitable mining of Leigh Creek’s brown coal were thwarted by technical and logistical difficulties (Klaasse 1997, chs 1, 2). It wasn’t until 1941 when coal supply to South Australia proved precarious that serious prospects for mining the coalfield were advanced successfully.

Figure 3 Champion of Leigh Creek coalfield, former premier Tom Playford (left) examines coal in an open-cut pit in 1944. Pictured with Gilbert Poole (Engineering and Water Supply Department), TM Carey (Zinc Corporation) and I Stewart (Commonwealth Coal Commission). (Photo N002297)

Former premier Tom Playford championed the cause to define the coal deposit’s extent and work out how best to proceed to mine it – drawing on public sector capabilities – in the Department of Mines, Engineering and Water Supply Department, South Australian Railways, the Factories and Boilers Department, Treasury through to the Chief Storekeeper (Klaasse 1997, p. 63; Fig. 3).

Following the start-up of production in 1944, coal was successfully tested in the Whyalla steelworks and used for trams, government institutions, including the Royal Adelaide Hospital, and an increasing array of industrial applications, dispelling criticism of Leigh Creek’s brown coal. When interstate shortages of coal prevailed, Leigh Creek coal kept the Osborne Power Station running, entrenching its value to the South Australian economy and community.

In 1946 Playford succeeded in nationalising the Adelaide Electric Supply Company Ltd when he secured support for the Electricity Trust of South Australia (ETSA) Bill. Continuing on a swell of political support, the government-owned ETSA took control of the coalfield in 1948 to secure coal supplies for power generation. In 2000, just over half a century later, operations at the power station and coalfield were privatised.

In 1954, the first ETSA-owned Port Augusta power station (90 MW) purpose built for Leigh Creek coal was commissioned, followed by another in 1963 (240 MW) and yet again in 1985 by a further expansion with the installation of the Northern Power Station. This culminated in the delivery of 544 MW of power from Leigh Creek coal.

With the expanded power plant, came the need to enlarge the coalfield and construct a retention dam to prevent flooding. Associated with this the township had to be relocated, and a new site for Leigh Creek was selected 22 km south at Windy Creek. Construction commenced in 1979, and by 1980 the first home was occupied.

Roughly 100 Mt of coal was mined from Leigh Creek, to a depth of 200 m using traditional open-cut mining methods. The early years of Leigh Creek saw a dramatic increase in production from 9,000 tpa in 1943 to around 444,000 tpa in 1949–1950. At full-scale operations the mine produced between 2 to 4 Mtpa of brown coal using conventional truck and shovel methods as well as terrace mining in the 1990s. Coal ore was crushed and stockpiled on site, then transported 250 km south by rail to the power stations.

In June 2015 Flinders Power’s parent company, Alinta Energy, announced it would cease mining by November 2015 as the operation had become uneconomic.

Formulating closure plan

The closure announcement in June 2015 set in motion an intensive period of planning towards mine closure and remediation, which was assigned to Flinders Power, then a subsidiary of Alinta Energy (Figs 4, 5).

Current and future potential environmental and social impacts had to be identified, risks assessed and prioritised for control, roles and responsibilities made clear, and a comprehensive program of works documented. The Leigh Creek closure plan documented culturally significant heritage sites and artefacts, and set out a robust community engagement plan and a management strategy.

In formulating its approved Mine Closure Plan, Flinders Power conferred with South Australia’s applicable regulatory authorities – mining regulators from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet (DPC), the Environment Protection Authority (EPA), SafeWork SA, the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR) through to Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation (AAR), and more.

Flinders Power credits the collaborative effort during the risk assessment phase as bringing essential clarity to the closure plan:

‘The joint risk assessment process enabled all parties to focus their attention on key risks associated with the closure, so clarifying the necessary resources to manage those risks’

Brad Williams, Program Director.

Communities and stakeholders were actively involved in the engagement program including the Adnyamathanha Traditional Lands Association (ATLA), services providers, residents, the Leigh Creek and Copley Progress associations, local and regional community and businesses interests, pastoralists and regional bodies.

Figure 4 Aerial view of part of the Main Series pit showing drop-structure channels (top left) designed to capture and direct surface water runoff to minimise disturbance of rehabilitated slopes. (Courtesy of Flinders Power; photo 416241)

Figure 6 During consultations about the remediation, the local and regional community voiced strong support to retain the retention dam for fishing and recreational enjoyment. (Courtesy of Flinders Power; photo 416242)

During consultation, community voiced a strong preference for the existing site retention dam to be maintained as a post-mine landuse asset and kept for public enjoyment (Fig. 6). The dam has become a wildlife refuge with several varieties of fish, shrimp and aquatic snails native to the Cooper Creek present. The regulator has responded with a plan for the dam to be kept, albeit with a re-engineered spillway to allow more water flow to return to the surrounding northern catchments following times of heavy rain, aided by the construction of a diversion channel. Public safety will be addressed through site access restrictions to a single location leading to a shallow beach historically used by the local community.

In broad terms the closure plan has focused on addressing, monitoring and tracking the success of approaches to deal with the health and safety of people, sensitivity of associated ecosystems, maintenance of water quality and flows in surface waterways, maintenance of water quality in groundwater and the creation of stable non-polluting and sustainable landforms.

This has translated into a series of detailed mitigation plans for public safety, pit wall stability, spontaneous combustion risk, retention dam integrity, surface water and groundwater management, preservation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage sites, and a means of dealing with existing infrastructure.

To reduce the safety risk of public access into mine areas, barriers or earth-based bunds will be constructed around mine pits, with the design incorporating surface water management. Careful planning will enable controlled access to the original town cemetery.

Reducing coal combustion risk

Each coal seam has a unique propensity to spontaneously combust depending on the complex interplay of variables. To tailor solutions for Leigh Creek, Flinders Power has drawn on their extensive site expertise and rich archive of historical mine information, and sought the counsel of leading industry experts (Flinders Power 2017, pp. 149–169) and independent advice by authorities.

Limiting the access of oxygen to coal is key to lowering the risk of spontaneous combustion. At Leigh Creek technical teams have achieved this by re-profiling waste dump slope in areas at high potential and likelihood for combustion, and then by applying and covering with non-combustible material (Fig. 7).

Re-profiling to reduce the angle of slopes acts to significantly reduce the ability of oxygen to permeate the dump, curtailing its ability to establish a convection cell. The cut-and-fill methodology inherently reduces particle sizing of the outer overburden layer and provides a compacted surface. Subsequently applying inert cover with a fine, clay-rich material further reduces the potential for water and oxygen ingress.

Controlling surface water movement is the next key step to reduce the potential for erosion of protective cover and maintain the short- and long-term stability of the rehabilitated areas.

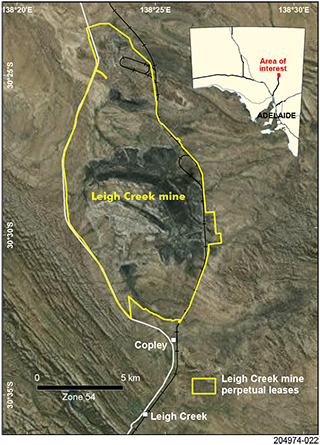

Infrared thermal monitoring is being used to gauge the success of the rehabilitated profile (Fig. 8), and this will continue as a post-closure monitoring procedure, aided by the use of aerial drone technology.

Figure 7 Collecting fine, clay-rich material that is non-combustible for use as a cover to reduce water and oxygen ingress. (Courtesy of Flinders Power; photo 416243)

Next step

While the majority of on-ground excavation and landform works are on target by Flinders Power to be completed by mid 2018, the team expect an active monitoring process to accurately demonstrate the closure strategies have been effective, with five years the likely period.

Mining regulator’s comments:

‘Casting to the future in five to ten years, the success of this project will be judged by the successful management and control of associated offsite risks, the preservation of mine history, including cultural sites, while maintaining public safety.

‘Leigh Creek mine has been so much a part of South Australia’s living memory and energy history, but in future the nearby surrounds will also be better appreciated for its rich Aboriginal heritage, diverse flora and fauna, like the yellow-footed rock wallaby along with emus and reptiles, 40 species of birds, and the native aquatic life that now inhabit the retention dam.’

Acknowledgements

Flinders Power, in particular Brad Williams, Peter Kelly and Paul Jones, are acknowledged for assistance with the article and supplying many photographs.

References

Klaasse N 1997. Leigh Creek, an oasis in the desert. Flinders Ranges Research, Eden Hills, South Australia.

Further information

Leigh Creek Coal Mine

Flinders Power

Leigh Creek Futures