If you ask anyone what mining looks like to them, they will likely describe a large hole complete with big yellow dump trucks and excavators moving tonnes of dirt – an ‘open cut’ mine, or dark underground tunnels filled with workers wearing helmets and headlamps – an ‘underground’ mine. These types of mines have historically been – and are still – the most common types of mines found across the world.

There are others – one of which is in situ recovery or ISR mining, a technique that has been used since the 1970s in Australia, the United States, Kazakhstan, China and Russia to mine potash, salt, uranium and copper.

What is in situ recovery mining?

In situ recovery mines use fluid to recover valuable minerals from the ground without digging and moving tonnes of earth in the same way that you would at an open cut or underground mine.

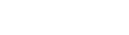

Instead, the in situ recovery mining process involves pumping lixiviant (mining solution) underground to mobilise valuable minerals from the geology that hosts them. The fluid, which is a mix of water and chemicals added to accelerate the mining process, is then pumped to the surface for the minerals to be recovered for sale. The remaining solution is then retreated and circulated back through the rock to recover more minerals. This process continues until the process no longer recovers a viable amount of minerals, and the mine is rehabilitated and closed.

Depending on the properties of the mineral deposit, the fluid which will most effectively liberate the minerals may be either acidic or alkaline, achieved by including chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide, sulfuric acid, baking soda, oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Figure 1 shows the in situ recovery process, showing the location of the mineral deposit, the circulation of fluids, and the wells placed around the mining zone that demonstrate control of the mining process.

Figure 1 Conceptual model of an in situ recovery mining process.

Because in situ recovery mining involves the circulation of fluid rather than the movement of rock, there is very little surface disturbance or generation of noise, dust or vibration that can be associated with open cut or underground mining.

Why then is in situ recovery not used for every mine?

Put simply, all mineral deposits are different, and located in different environments, and in situ recovery is only a viable mining method in some situations.

In situ recovery mining is appropriate in situations where:

- water can move freely through the geology which hosts the minerals

- those minerals are readily mobilised into solution and can be moved using water and other reagents

- the minerals can be recovered from that solution

- the solution can be contained and strictly controlled in the local environment

- the process can be managed without unacceptable damage to the environment

- the overall process can be undertaken economically.

Because in situ recovery methods are not suitable for every mineral resource, the technical work that must be undertaken by a company and government to evaluate potential in situ recovery mines is substantial.

Studies routinely involve years of investigations, including drilling into and around the mineral deposit, sampling and mapping groundwater in and around the local area, and detailed laboratory work to evaluate whether in situ recovery is a suitable approach for a particular deposit.

If preliminary studies are favourable, a carefully regulated trial is usually undertaken to validate the results of those investigations, and to prove that the deposit can be effectively and safely mined before there is any decision to allow mining to proceed.

The South Australian and Commonwealth governments have been regulating in situ recovery mining operations since the late 1990s and are a leading contributor to global regulatory practice for the development, operation and closure of in situ recovery mining operations, as described in Australia’s in situ recovery uranium mining best practice guide (PDF 4.7 KB)

Whilst to-date in situ recovery is commonly only used in Australia for mining uranium, and in large scale operations across the globe for mining potash, salt, uranium and copper, global interest is growing in its use for other minerals such as nickel, silver, zinc, and cobalt. Research organisations such as Australia’s CSIRO are partnering with government and industry to explore further opportunities for the safe and successful use of in situ recovery mining around the world.

Aerial image of Beverley uranium mine, South Australia. (Courtesy of Heathgate Resources)